The Hearts of Iron series might be the most ambitious series of videogames ever produced for a general audience. What they attempt to do is compress the largest and most complicated war in human history into something which can be controlled and directed by a single person.

The Hearts of Iron series might be the most ambitious series of videogames ever produced for a general audience. What they attempt to do is compress the largest and most complicated war in human history into something which can be controlled and directed by a single person.

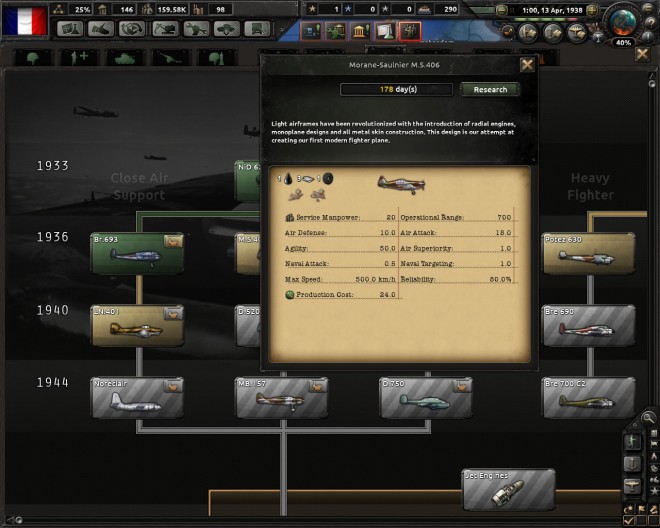

All aspects of the war effort are at the player’s disposal, from the direction of production and research to the disposition and command of troops. The level of simulation is impressively deep, although understandably occasionally somewhat skewed. HoI is the closest that videogames come to being a doctoral thesis on the reasons that world war two was won and lost.

From my armchair I have directed campaigns all over the world. From the Sahara desert to the jungles of Borneo I have shepherded troops into battle, carefully laying plans for their supply and upkeep, assessing the enemy’s strength and pressing their weak points. Map of the world is remade into a canvas for imperial conquest, heroism and the struggle for democracy. I have never played a game of Hearts of Iron that did not leave me with a story to tell, a strange new history to examine.

Today I would like to present you one of these strange histories. A history of WW2 that diverges from our own, starting with a what-if that I played out in a game of Hearts of Iron four; what if France had stood up to Germany in 1936? This is part one of my (somewhat embellished account) of what occurred.

In a hotly contested cabinet meeting held in cold room beneath a grey Parisian sky on the 7th of march 1936, prime minister Albert Sarraut and minister for war Louis Maurin debated how to respond to the news that three German battalions were marching to re-take the Rhineland.

The French army (roughly 320 thousand men) could, and did, outnumber the Germans. However Gamelin insisted any aggressive action would still have to involve a general mobilisation of French armies, a costly measure which threatened to bankrupt France, and possibly cause a revolution. The cabinet agreed that some response was necessary, Pierre-Étienne Flandin, the foreign minister, favoured armed intervention using the structures set up by the, by now almost defunct, League of Nations. This would draw in support from Britain and would give allow for a quick return to the status quo after the cessation of hostilities. However, it was clear from communiqués from London, the British were opposed to any course of action that might lead to full scale war. Flandin, frustrated with the British and acting in an uncharacteristically decisive and rash manner, unilaterally sent a telegram to Berlin demanding that German troops leave the Rhineland or face war.

It was one of the greatest diplomatic gambles in French history, and one that Flandin had no authority to make on his own. It cost him his career when Sarraut sacked him the next day. In the event however, Hitler backed down, and it was Sarraut’s government that was left holding the can. Persuaded by his generals that a war over the Rhineland could not be won without further re-armament, Hitler withdrew his forces and retired to lick his wounds. The response from the French public was overwhelming, war had been avoided by the threat of French arms. While the population was still deeply scarred by the memory of the first world war, here were results that a degree of militarism could lead to success without French troops having to set foot on German soil. Of course praise was not universal, and there was some public outcry against this brutish display of force. However, such outcry was mostly limited to the far-left, including the communists. While the Communists had no love lost for the 3rd Reich, they complained that the unilateralism of Flandin’s telegram revealed the true fascism that lay at the heart of the Republic.

Flandin’s telegram caused a major scandal in the press when details of the negotiations were leaked . Sarraut was derided as a coward, being christened “The Mouse” in the Parisian press. Within weeks the government had fallen and was replaced by a popular front government headed up by the resolute seeming Édouard Daladier. He was a veteran of the first world war, a stout man, known to his supporters as the “bull of Vaucluse”, for his wide neck and shoulders. He projected the atmosphere of a man entirely in control of himself and his surroundings (how deserving he is of this reputation is a matter for debate). After the “Flandin scandal”, Daladier made great hay out of deriding Sarraut, calling him weak and foolish. Daladier seemed a natural replacement, the muscular face of the left wing of the French political establishment.

While France had bought herself an advantage in the coming war, the French army was still something of a paper tiger. While it was stronger than the German army in early 1936 (roughly 320 thousand to 300 thousand men), it quickly lost numerical superiority as the year ran its course, with German manpower bordering on 500 thousand men by the end of the year. Further, the French army had no clear doctrine for the use of its many tanks, nor did there seem to be any clear idea of how a war with Germany would actually be won.

Maurice Gamelin, commander of French forces, was fixated on a doctrine that was predicated entirely on his opinion of where the French army went wrong in WW1. Gamelin was credited, in part, for the victory on the Marne in 1914, and had enjoyed a distinguished career. He was an aloof man, proud and not fond of criticism. His vision of the next war was as a re-run of the first in almost every respect, which lead to a belief in the possibility of a forward and offensive war against the 3rd Reich. The fact that the German army had backed down in the face of the French army was a surprise for many in its junior command structure who were convinced that the Germans were completely unafraid of them. Re-vialised by their un-expected strength, but worried that Gamelin rated France’s offensive power too highly, these junior officers were soon in almost total revolt against their stayed commander. Staff papers speculating on the course of the next war were soon flooding out of the staff collage and into the press, leaked by disgruntled officers.

The French army was traditionally a instrument of the right-wing in France. Its high command was exceptionally conservative and fearful of Communist infiltration in the junior ranks. This meant that plans for the expansion or reform of the army were often viewed with suspicion from the higher echelons of command as they would require drafting in huge quantities of “regulars”, new men to the army who were more likely to be left-leaning (as the majority of French society was).

Daladier faced some difficult choices. On one hand he had promised that he would not, as a politician, intervene in military matters; on the other hand he was now faced by a wave of left-wing militarist populism which demanded that France flex its military muscles and fully re-arm in defence of Liberté, Egalité and Fraternité. In the January of 1937 a paper by Alphonse Juin, at that point a battalion commander serving in Morocco, speculating that France’s current war plans would culminate in defeat in a war with Germany was leaked to the press. Gamelin’s battle plans included a forward defence in Belgium, essentially stripping the French forces of all their reserves at a stroke and leaving the front line almost entirely open at the Ardennes. Juin concluded that under such conditions France would be easily invaded and have to capitulate within the year. This caused public uproar, while Gamelin demanded that Daladier execute the young offices responsible for the leaks. Unfortunately for Gamelin, Daladier had correctly guessed the way the wind of public opinion was blowing and called his bluff. The young officers were re-assigned away from the staff collage and Gamelin himself was effectively exiled to command the French forces in Lebannon. He did not resign, eventually retiring from the armed forces in 1950.

In February, after a period of vacillation, Daladier finally got off the fence and intervened fully in military matters. In a stirring speech delivered at Versailles, Daladier announced that he would give France “the means and the strength to stand, alone if necessary, against the rising tide of fascism”. The speech resonated around the world, causing a surge in pro-French sentiment in the USA, while causing the British foreign office to issue a caution against “rash and poorly prepared action in Europe which could lead to a world-wide war”. Hitler, in response, gave a speech comparing Daladier to an “elderly and toothless dog, barking in-vain at a new world order”.

In practical terms Daladier’s speech meant increasing funding for military re-armament and implementing changes within the French command structure. The French army would increase in size, it would favour new ideas and the old guard would find themselves swamped with left-leaning regulars. Factories were constructed in mainland France, as well as secretly in Algeria. With Gamelin’s exit from high command, Maxime Weygand was recalled from retirement to serve. A figurehead for the right-wing in France Weygand was no friend of the young officers cadre, and made life exceptionally difficult for Juin and Tassigny, whom he regarded as “closet communists”. However, Weygand was also a political animal, and decided that his best course of action would be to hoist the young generals on their own petard. In April, Juin found himself catapulted through the ranks to the generalship of French forces guarding the Belgian border.

Juin was now in joint command of 75% of the French armed forces with general Jean de Lattre de Tassigny. Jean de Lattre de Tassigny, commander of the 5th army defending Alsace, was known for his personal bravery. He was repeatedly wounded in World War 1, winning eight citations for bravery. A favourite of Alphonse Joseph Georges, a forward thinking officer who respected Tassigny’s independent nature, he had enjoyed a fast advancement in the interwar years. Juin and de Lattre were an effective working partnership, and with de facto control of most of the French army, set about trying to prepare for the next war.

In 1938 studies, directed by general Henri Giraud, suggested that with the current level of increase in French industrial production—significantly slowed by the need for compromise with factory workers who demanded higher wages—France could not hope to fight an offensive war until 1941. Giraud therefore that the Belgian border be heavily fortified and that the standard training for the French infantryman be heavily modified. Previous training had emphasised top-down command and control under the direction of the commander in chief. The new doctrine would instead emphasise small unit tactics and training of the kind already practiced by French Alpine divisions in Savoy. The idea would be to draw the enemy into defensive pockets where they would be battered with overwhelming fire power. To this end Juin and de Lattre began re-training French forces on the German and Belgian borders in the image of the Alpine divisions. Through backchanneling with Daladier, avoiding the hostile Weygand altogether, de Lattre managed to secure extra battalions of artillery, as well as support detachments of anti-aircraft and anti-tank weapons.

In Giraud’s vision of the new army, each division was to be able to operate with a maximum of independence. Instead of trying to hold lines of trenches, the army would operate a defence in depth drawing the enemy into long and costly local battles among heavy fortifications. Divisions would be arranged in so that German forces would find themselves unable to break out without prolonged sieges of independent but mutually supporting strong points. Artillery was easier to produce than tanks, and therefore it was reasoned that as a stopgap measure the army could be heavily bulked up by the addition of guns. All possible arms would be brought to bear on the enemy at once, with anti-aircraft batteries being designed with the dual role of airspace defence and fire support for troops in mind.

In 1934 Charles de Gaul had written a paper calling for the concentration of French armour into a small number of divisions, which would act to break through enemy lines and disrupt their communications. Gamelin had dismissed de Gaul’s ideas but with a change at the top the army Juin and Tassigny pressed for the creation of a tank arm. The problem was that the number of tanks which would be needed for any effective offensive would not be available for years. Thus the army resigned itself to entirely defensive war planing for at least three years. The army would hold the Germans at the border until a large enough number of tanks had been produced in order to form an effective striking force, which would reach out through Belgium and roll around behind the German forts on the Siegfried line. It was a plan that predicted the war would last at least five years.

The change at the top lead to a vast expansion of the French army, with ten new divisions being formed in the latter half of 1937 alone. In March 1938, in response to the lacklustre Leauge of Nations response to the German annexing of Austria, the maginot line was extended to cover the Belgian border (which caused an official complaint from the Belgian ambassador in Paris). Although not as strong as the line on the German border, the Belgian Maginot—complete by 1939—included a vast series of concrete emplacements, trenches and tank traps. At the same time a huge enlargement of the French airforce with fighters and light bombers was recommended by Giraud in order to prevent an “encirclement by air”. Also established was a centre for decryption and analysis of enemy communications in Alsace, the “Département du Grenouillage”, which grappled with the German enigma code.

French military preparations did not just include changes to the army and its tactics, they also included a raft of diplomatic measures. Flandin had been retained by Daladier after the telegram scandal due to his public popularity. Flandin was an unremarkable man, born in Paris and trained as a lawyer. Having fought in the first world war Flandin was dedicated to trying to protect France from German aggression. Writing in his post war memoirs Flandin referred to his famous telegram:

“Something which I did not so much decide to do as something that flowed through me in a fit of pique. It was as though some higher power was controlling my actions, it was a mere stroke of luck that it turned out in the country’s favour. I thank God for it.”

After being re-instated as foreign minister, Flandin determined to bring the British into a closer alliance. It had been British reluctance which almost allowed the Germans to march into the Rhineland, but without them the defence of the French state against Hitlerite aggression looked doubtful. The British were needed to secure trade with America, the French navy being thoroughly established as a Cinderella service (in order to free up money for re-armament of the Army, all construction on French vessels had been halted in perpetuity). Flandin therefore went on a charm offensive, trying to convince the British that appeasement was not sustainable. This proved almost impossible, as the British gave in to German demands at the Munich conference in 1938. However, Flandin did succeed in repairing the alliance that he had endangered with is rash actions. In January 1939 British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlin agreed that Britain would defend France in a war caused by German aggression.

French preparations for a defensive war were mostly complete by March 1939, with just barely enough military equipment being produced to fully equip all front-line battalions. French military production of rifles, artillery pieces and field guns had increased tenfold in three short years. Equipment and men were still scarce however and Juin in particular was still deeply worried about the prospects of winning a war against Germany, in his diary that April he wrote:

“Preparations good in Pas-de-Calais, morale excellent… [preparations] along the rest of the line still patchy, some units lacking heavy artillery. All officers expect to lose the Ardennes when the Germans come, but we shall not lose them quietly”.

Juin and Tassigny would have their preparations tested fully in June, when world tensions would come to a head over Poland. The war, however, would follow a path that neither of them could have predicted.